CAREER EVOLUTION Former Volusia Sheriff’s Spokesman Pursues Passion Into Classroom

Date Added: September 14, 2014 3:41 pm

September 15, 2014

By Annie Martin

annie.martin@news-jrnl.com

CAREER EVOLUTION

Former Volusia sheriff’s spokesman pursues passion into classroom

ORANGE CITY — Phineas Gage was a new man after a rock-blasting accident drove a large iron rod completely through his head.

ORANGE CITY — Phineas Gage was a new man after a rock-blasting accident drove a large iron rod completely through his head.

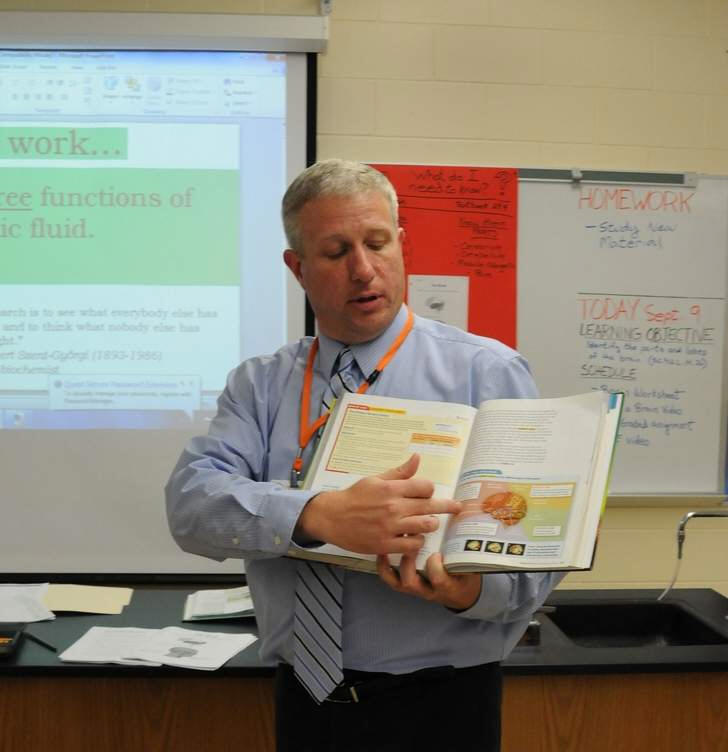

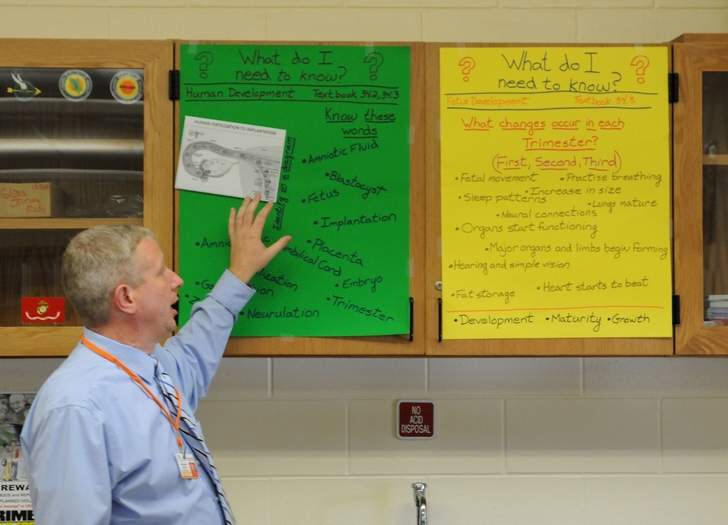

Facing an audience of fidgety teenagers, first-year teacher Brandon Haught recounted the oft-told tale of Gage, a 19th-century railroad foreman. He spoke over the sound of chairs swiveling, pens tapping against lab tables and whispers anticipating the final bell.

Haught, 44, recently left his post as the assistant public information officer at the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office to teach biology at University High School in Orange City. He swapped snoopy reporters for sleepy students. Police reports for lab reports. Arrest records for attendance records.

Becoming a teacher has been a lifelong dream for Haught, who said he loved science in high school but didn’t feel his math skills were strong enough to pursue a career in that field. Haught said he’s been both a teacher and a student during his first year in his new role. Classroom management — ensuring lessons run smoothly and minimizing disruptions — is a stumbling block for many new teachers, including Haught.

Becoming a teacher has been a lifelong dream for Haught, who said he loved science in high school but didn’t feel his math skills were strong enough to pursue a career in that field. Haught said he’s been both a teacher and a student during his first year in his new role. Classroom management — ensuring lessons run smoothly and minimizing disruptions — is a stumbling block for many new teachers, including Haught.

“I did have some problems within the first week of school,” he said. “You just learn the hard way. One thing you can do is keep them busy — the bell rings, you get to work and you don’t let up until the next bell rings.”

At the end of his own high school days, Haught said he didn’t know what he wanted to do, so he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, where he focused on public relations for 12 years. He spent the past decade at the Sheriff’s Office, fielding calls from reporters and handling public records requests.

“While I was at the Sheriff’s Office, I realized that the career of public affairs, public relations chose me — I didn’t choose it,” said Haught, who lives in Port Orange.

Years after settling into that career, Haught found his passion. He earned a bachelor’s degree in science education in 2011, leaving the Sheriff’s Office for three months so he could student-teach at Eustis High School. After hours, he volunteered as the communications director for Florida Citizens for Science, a nonprofit organization that promotes science education. He authored a book, “Going Ape: Florida’s Battles over Evolution in the Classroom,” which was published earlier this year. A copy of the book is propped in a cabinet behind a glass window in his classroom.

Newcomers like Haught are in good company this year: Volusia County hired close to 500 teachers over the summer, and the ranks likely will continue to grow. The number of elementary, secondary and special education teachers in the U.S. is expected to grow by 332,500 between 2012 and 2022, according to the Department of Labor. Teachers in Florida public schools must have bachelor’s degrees and certification in the grade levels and subject areas where they teach, though many colleges offer a fast track for people who have degrees in other fields and want to pursue careers in education.

Switching to teaching meant a slight pay cut for Haught, but he said that didn’t bother him. Starting pay is about $36,000 for Volusia teachers with bachelor’s degrees.

Haught’s path to teaching was circuitous, but that’s not unheard of, University Principal Dennis Neal said. People who pursue teaching mid-life are often especially motivated because it’s a calling for them, Neal said. Teachers who are on their second or third career are able to inject their life experiences into the classroom.

Not every student is naturally drawn to science, Haught said, but he hopes to lean on his own experiences to make the subject more meaningful. Between his time in the military and at the Sheriff’s Office, he has a wealth of material to discuss with students.

Not every student is naturally drawn to science, Haught said, but he hopes to lean on his own experiences to make the subject more meaningful. Between his time in the military and at the Sheriff’s Office, he has a wealth of material to discuss with students.

In the aftermath of the 1993 Sunset Limited train wreck near Mobile, Alabama, Haught helped with rescue and recovery efforts, including removing dead passengers in body bags. He’s had an intimate view of homicide

sites and met with the family and friends of the victims. Haught was an employee on the sixth floor of the federal building in Oklahoma City when a bomb detonated there in 1995, killing 168 people and injuring hundreds more. He wasn’t at work the day of the attack, but lost several coworkers that day. He’s traveled to Japan, the jungles of Panama, and the Sahara desert. He’s seen how other people live, including many who endure intense hardship.

Haught said he knows he won’t bestow a love of science on every student, but he hopes he’ll at least give them an appreciation for the topic.

“Someday, something might happen to you or someone you love,” he said. “Wouldn’t it be nice, when the doctor is talking to you, to understand what they’re saying?”

But many new teachers, Neal said, are surprised by the daily demands of the job. During the hiring process, he’s forced to guess who can handle a career in the classroom, and he predicts Haught will remain cool when students test his patience.

“In Brandon, what I thought would serve him well is he is used to thinking on his feet and handling high-stress situations on a regular basis and that will serve him well as a high school teacher,” Neal said.

But it’s a different type of stress, Haught said. At the Sheriff’s Office, he occasionally handled 2 a.m. phone calls and all-nighters when news broke. Since school started Aug. 18, Haught hasn’t had a full day of rest, staying at school until at least 5 p.m. each night and spending weekends planning lessons and grading papers. Haught’s first month on the job has been especially stressful, he said, because he didn’t have much lead time. He was hired a week and a half before classes started.

Haught recently incorporated the story of Gage’s injuries and improbable survival during a lesson about the role of the frontal cortex, a part of the brain that’s linked to judgment and temperament. Gage was a responsible, hard-working 25-year-old at the time of the accident. After the incident, he was reckless and irritable. Scientists attribute Gage’s drastic personality changes to the brain damage he suffered.

Haught’s career transformation wasn’t as life-changing as Gage’s, but it has been an adjustment. Regardless, he urges other mid-life visionaries to take the leap, too.

“Don’t be afraid of it,” he said. “I could have just easily said, ‘I’ll put in my time, retire, go and pursue other dreams.’ But why? You only live once. If you really want to do it, do it.”